As Andrea Baccarelli, the dean of Harvard’s School of Public Health, prepared to open a virtual town hall earlier this month, members of the university’s graduate-student union gathered for a watch party with “Baccarelli Bingo” cards. The game boards were filled with phrases the dean was expected to use: “these are difficult times”; “i know it’s not a satisfying answer but we don’t know”; “… which is why we must be innovative!” At the center of the grid was a free space, bedazzled with emojis, that read, “no meaningful commitments made.”

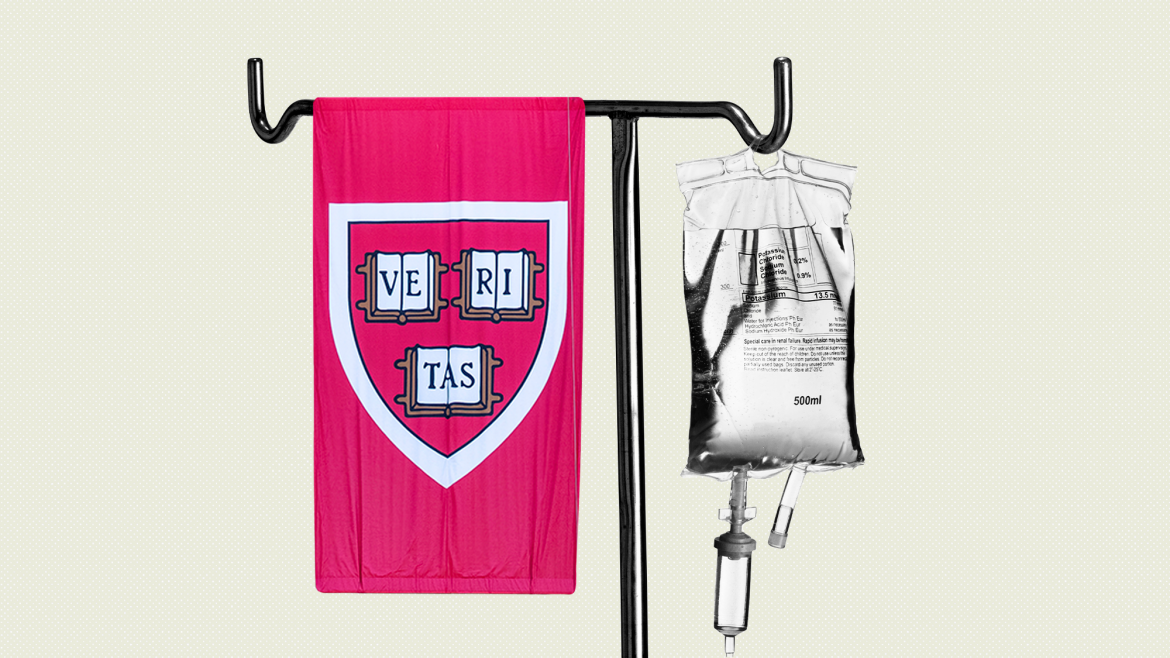

Baccarelli’s stated goal was to provide an update on the school’s financial crisis. Of Harvard’s schools, HSPH has been by far the most reliant on government grants—and so was the hardest hit by the Trump administration’s cuts to federal research funding. In the spring, essentially overnight, the school lost about $200 million in support. Although a federal judge has ruled that those grant terminations were illegal, the school’s future relationship with the federal government remains uncertain. Long-term survival for HSPH would require dramatic change, Baccarelli said at the town hall: It needed to become less dependent on federal funds. In the process, it would have to cut $30 million in operations costs by mid-2027 and potentially slash up to half of its scientific research. HSPH is one of the most consequential public-health institutions in America: The school once contributed to the eradication of smallpox and the development of the polio vaccine, led breakthroughs linking air pollution to lung and heart disease, and helped demonstrate the harms of trans fats. If the Trump administration’s aim has been to upend American science, HSPH is a prime example of what that looks like.

But the school’s dean, too, has become something of an emblem—of how unprepared many scientists are to face this new political reality. At the town hall, Baccarelli had to address his controversial work linking acetaminophen—Tylenol—to autism and answer for how he’d communicated with the Trump administration about it. (Another Baccarelli Bingo square: “acetaminophen mentioned.”) At a press conference in late September, Donald Trump and several of his top officials announced that they would update Tylenol’s labeling to discourage its use during pregnancy, leaning heavily on Baccarelli’s research on the subject and on expert witness testimony he’d given. “To quote the dean of the Harvard School of Public Health,” FDA Commissioner Marty Makary said, “‘There is a causal relationship between prenatal acetaminophen use and neurodevelopmental disorders of ADHD and autism spectrum disorder.’”

Plenty of the school’s faculty were taken aback to hear Trump officials warmly referencing their dean, especially given that Tylenol’s connection to autism—a complex condition with many contributing factors—is shaky at best. Karen Emmons, an interim co-chair of HSPH’s department of social and behavioral sciences, told me she almost crashed her car when she heard Makary quoting Baccarelli on the radio. Many were also surprised to learn, from press reports, that Baccarelli had fielded calls about his research from Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and National Institutes of Health Director Jay Bhattacharya earlier in September.

The dean’s interactions with the administration quickly became a new vulnerability for the school. As other experts criticized the methodology of Baccarelli’s work on Tylenol and called his claims about causality unfounded, Baccarelli began to look like a biased researcher, allied with the same political leaders “who are starving us of our funding and basically killing the school,” Erica Kenney, a nutrition researcher at the school, told me. In the view of many faculty members, Baccarelli had undermined the public position Harvard spent months cultivating—as a beacon of academic integrity, unwilling to bend to the administration’s political pressure. (Baccarelli declined interview requests for this story and answered a series of in-depth questions with a brief statement saying that he looked forward to “continuing the work of building a sustainable future” for the public-health school.)

At the town hall, Baccarelli seemed to recognize these consequences. “I’m really sorry about the impact this has had on our school,” he said. But he was also defensive, describing himself as a researcher who wanted to explain the value of his work and help set evidence-based policy. He had spoken with the administration as a scientist, not as a Harvard dean, he said, and hadn’t anticipated that Trump officials would focus so pointedly on his affiliation with the school. His instinct, in other words, was to treat science as severed from politics. He seemed unaware of how unrealistic that split now is for American scientists.

Some nine months into the Trump administration’s assault on academic science, Harvard’s public-health school has just about everything going against it that an American academic institution can. It is part of Harvard, which the administration has accused of failing to protect students from anti-Semitism. It has excelled in several fields that the administration has declared unworthy of federal funds: infectious disease, health equity, climate change, global health. About half of the school’s faculty contributes in some way to international research, which the administration has also taken a stand against. Many HSPH researchers are themselves from other countries—including roughly 40 percent of the school’s students—and their ability to stay here is uncertain under the Trump administration’s immigration policies.

Historically, nearly half of HSPH’s revenue and 70 percent of its research funding have come from federal grants. And unlike academics supported largely by tuition or endowments, HSPH researchers typically have had to bring in nearly all of their own research funds, including to cover their own salaries and those of staff and trainees. “Faculty members essentially function as a small business,” Jorge Chavarro, HSPH’s dean for academic affairs, told me. When researchers’ federal income dried up, they had to shrink those businesses. David Christiani, a cancer researcher, laid off four staff members; to pay the rest of his people, he told me, he’s blown through nearly half of the roughly $900,000 in discretionary funds that he’s accumulated since the 1990s. Roger Shapiro, an infectious-disease researcher, fired half of a research team in Botswana that has been studying the use of HIV antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy. Erica Kenney’s team will likely shrink from about a dozen people to three. And the school’s incoming cohort of Ph.D. students this year was half its usual size. (In 2018, I earned a Ph.D. in microbiology from Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. My thesis adviser, Eric Rubin, holds an appointment at the public-health school.)

When the funding crisis hit, Harvard distributed emergency funding across its schools. But what reached HSPH faculty offered little relief—in Christiani’s case, it was “too small to have kept anything going other than literally the freezers and some data management,” he told me. (The office of the Harvard University president did not respond to a request for comment.) The public-health school has put limits on the amount of discretionary funds that faculty can spend to keep their research going, to ensure the longevity of those resources during the crisis. “This is supposed to be the most flexible amount of money you have, so people try to save it for as long as possible,” one faculty member, who requested anonymity because they are not a U.S. citizen, told me. To plug the gaps, faculty have been frantically applying for nonfederal sources of money. But whereas grants from the NIH could total millions of dollars, many foundation grants come in the tens of thousands, not even enough to sustain a single postdoctoral fellow for a year.

As their professional world fell apart, many staff, students, and faculty waited for Baccarelli to articulate a clear path forward. He left the task of divvying up emergency funds to HSPH’s nine department chairs, and many researchers grew frustrated as different parts of the school scrambled to make ends meet in different ways. In one department, at least one faculty member has used personal funds to cover trainees’ travel expenses; the biostatistics department has pushed at least 10 Ph.D. students to do data-analysis externships in exchange for coverage of stipends. Across the school, three senior lecturers and three tenure-track junior faculty members have been notified that they will likely be terminated in 12 months, unless they secure alternative funding.

Some faculty members took those notices as a clear indication of HSPH’s more cutthroat future. One, who requested anonymity to speak about the school’s strategies, felt relatively secure because the school would “forfeit about $900,000 of overhead if they got rid of me,” they said. “When you become a financial liability, they cut you loose.” (Stephanie Simon, the school’s dean for communications and strategic initiatives, told me that prospects for future federal funding don’t motivate potential terminations, but also that grant reinstatements could prompt the school to rescind the notices for the tenure-track faculty.)

Baccarelli has repeatedly declined to say how many people the school has laid off this year, a common point of frustration among the HSPH scientists I spoke with. “So many of us have left, and you can’t tell us the impact?” said Matthew Lee, a former HSPH postdoctoral fellow who lost his position this summer because of the funding crisis. At the town hall, Baccarelli said that the university had asked him not to share those details. But he did share that HSPH had already cut $16 million from its operations budget, $7 million of which accounted for losses in personnel.

This was the path forward. In the brief statement he sent in response to my questions, Baccarelli said that he had “developed and communicated a strong vision for the future of the school.” The statement linked to a strategic vision on the HSPH website, which acknowledged that the school “cannot maintain the status quo” but asserted that it would emerge as “a focused, resilient, and unambiguously world-class school of public health.” Left unsaid was that it would almost certainly be a smaller, less enterprising one.

In many ways, Baccarelli, who assumed the deanship at the start of 2024, has limited power: He can’t force the Trump administration to relinquish funds, or raid the pool of money that Harvard University holds centrally. Still, for months, many trainees and faculty have been calling for their dean to “stand up more forcefully” to the administration’s siege on science and defend his school’s most vulnerable researchers, Sudipta Saha, a Ph.D. student at HSPH and the vice president of Harvard’s graduate-student union, told me. Before the town hall, the school’s faculty council conducted a poll—unlike anything they’d seen before, several faculty told me—about the dean’s ability to do his job and the impact that the Tylenol debacle will have on the school. (The results have not been made public, but at the town hall, Baccarelli described the feedback as “very direct.”) Several of the faculty I spoke with defended the dean. “He did nothing wrong,” David Christiani told me; Karen Emmons and Erica Kenney emphasized that they were sympathetic to his plight. But most HSPH researchers I spoke with said they were deeply frustrated with him.

To his critics, Baccarelli’s recent actions have revealed how willing he is to play fast and loose with scientific certainty, at a time when much of the scientific establishment has denounced the Trump administration for doing exactly that. Baccarelli’s research focuses on topics such as air pollution and aging, but for years he has had a side interest in Tylenol use during pregnancy. In 2023, he gave expert-witness testimony on behalf of plaintiffs suing the maker of Tylenol, for which he was paid about $150,000 and spent some 200 hours preparing. In that testimony, Baccarelli asserted that taking the drug during pregnancy was not just linked to neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism but probably caused them. Neither his own research nor others’ has demonstrated such a strong conclusion, and the presiding judge picked up on that. Although Bacarelli was “the plaintiffs’ lead expert on causation,” she noted, he had co-authored a study in 2022 arguing that more research was needed before changing recommendations for using Tylenol during pregnancy. She ultimately excluded his testimony.

Baccarelli later seemed concerned about how he’d come off in the case, Beate Ritz, an epidemiologist at UCLA who studies neurodevelopmental conditions, told The Atlantic. According to Ritz, Baccarelli approached her at a conference and explained that he wanted to write a paper to clarify why he’d concluded that Tylenol should be used cautiously: He had been accused of being in it for money, and hoped to set the record straight. Ritz agreed to collaborate with Baccarelli. Their resulting manuscript, published in August, stopped short of saying that Tylenol use during pregnancy caused autism, but argued for a strong link between the two. Since the Trump administration thrust the study into the limelight, several other scientists have lambasted it, saying it overemphasizes evidence that supports the authors’ preset biases. (Ritz told The Atlantic that she asked Baccarelli and her other co-authors to correct an early version of the paper because it gave undue weight to lower-quality studies. But she stands behind the final version.)

When Kennedy called, Baccarelli wanted to promote his findings as any other researcher would, he said at the town hall: “As a scientist, I felt it was my responsibility to answer his questions.” He said he had not discussed the school’s financial situation with the administration. He also declined to attend the press conference on autism; instead, he released a statement that day noting that further research was needed to determine a causal relationship between the drug and autism, but advising “caution about acetaminophen use during pregnancy.” (Andrew G. Nixon, the director of communications for the Department of Health and Human Services, did not answer my questions about the administration’s association with Baccarelli, but acknowledged that some recent studies other than Baccarelli’s “show no association” between Tylenol and autism. The administration’s current guidance “reflects a more cautious approach while the science is debated,” he wrote.)

Baccarelli’s intentions were understandable, Emmons told me: “He doesn’t want to give up his science.” At the same time, though, “when you’re a dean, you’re always a dean.” Baccarelli’s assumption that he could selectively cleave himself from his role at the school, several HSPH researchers told me, was at best clueless and politically unsavvy. At worst, it represented reckless neglect of his duty as the primary steward of his school’s reputation and future. Even in a less politically charged climate, Baccarelli’s controversial paper and overzealous witness testimony might have blemished his reputation. Under current conditions, they cut against his own vision of leading a world-class institution—which requires proving to other parts of the research enterprise that the school has maintained its commitment to scientific rigor.

Prior to this year, many HSPH researchers saw the school’s reliance on federal funds as a strength. Government support was exceptionally stable, and HSPH researchers were exceptionally good at winning it. By Harvard’s standards, the school’s endowment was not its primary boasting point—public-health alumni don’t tend to become billionaires —and in times of wider financial turmoil, HSPH remained well insulated, Amanda Spickard, the associate dean for research strategy and external affairs, told me. Now, for the first time, the school is confronting the risks of sourcing half of its operating budget from a single entity.

The government was public health’s ideal funder in part because it could play science’s long game: funding research that might not be immediately profitable or even beneficial. That pact is now broken, and as the school seeks alternative routes, several researchers worry that some of the most important science will be the fastest to fall by the wayside. If, as some faculty suspect, more commercializable research is likelier to survive at the school, HSPH also risks abandoning a core public-health mission—meeting the needs of the underserved—and detracting from Baccarelli’s own strategic vision of building “a world where everyone can thrive.”

I asked multiple faculty members in top leadership roles how HSPH planned to deal with these imbalances. None of them delivered satisfying answers. Spickard and Jorge Chavarro both mentioned getting faculty to think more creatively about pursuing funding. Both also acknowledged that some faculty will lose out more than others. (Emmons, the interim department co-chair, suggested that making research more interdisciplinary could appeal to funders across a wider range of fields.) Chavarro also said that HSPH leadership planned to clarify which of the school’s decisions are temporary, emergency measures versus actions that will guide the school long-term. But when I asked for examples from each of those categories, he hesitated, and ultimately named only emergency actions.

Although more than a month has passed since a federal judge declared the grant terminations at Harvard illegal, money is only just starting to trickle back to the public-health school, and several faculty told me they still don’t have access to their funds. (An internal communication sent by Baccarelli last week indicated that the university was still “in the process of reconciling the payments.”) HSPH has also been cautious about lifting spending limits on its faculty, in part because Harvard worries that the administration will continue to appeal the judge’s decision, or otherwise renew or escalate its attacks, Christiani told me. Late last month, HHS referred Harvard for debarment, which would block the institution from receiving any federal funds in the future.

Many HSPH scientists expect that this is far from the end of the most difficult era of their career. A few pointed toward William Mair, who studies the links between metabolic dysfunction and aging, as one scientist already stretching to do the kind of interdisciplinary work that might help the school survive. In recent months, Mair has been reaching out to colleagues across the school to collaborate on a healthy-aging initiative that will draw on multiple public-health fields. But Mair, too, has had to whittle his lab down to just five people and shelved many of the team’s more ambitious experiments. Originally from the United Kingdom, he came to the U.S. nearly 20 years ago for his postdoctoral fellowship, then stayed in the country that he felt was the best in the world at supporting science. (He became a citizen earlier this year.) “I don’t want to leave this community,” he told me. “But every minute I stay here at Harvard is currently detrimental to my own science career.” The university that once promised to buoy scientific aspirations now feels like a deadweight.

Tom Bartlett contributed reporting.